This spotlight comes from one of downtown Dubuque’s civic landmarks: the Hotel Julien Dubuque. This site has hosted travelers for over 180 years and, over time, has experienced many changes in management and practices. In this spotlight, we explore clues used to date this document and expand its context.

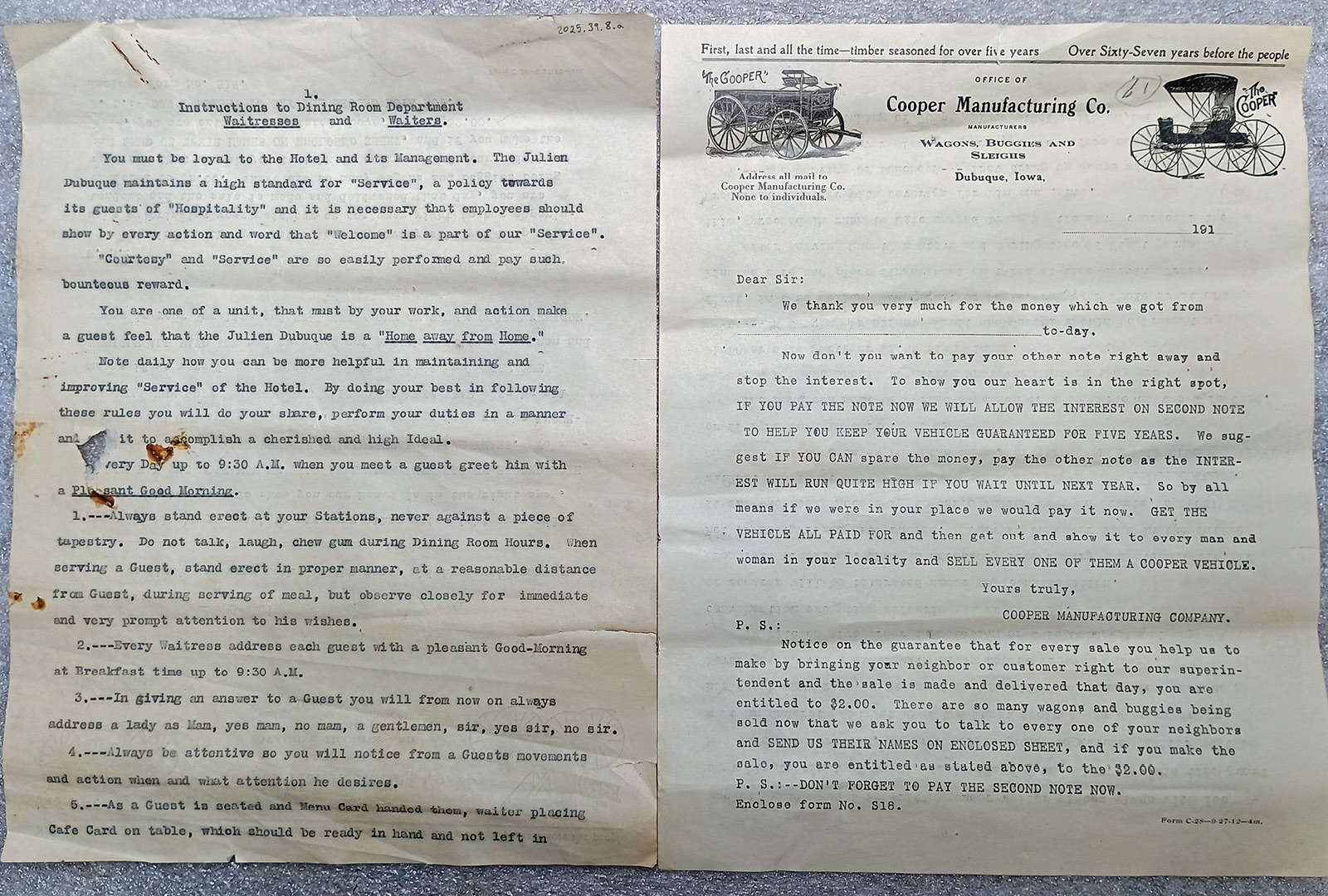

These six pages detail instructions for waitstaff in the hotel’s dining room. The foremost instruction is: “You must be loyal to the Hotel and its Management.” The document then outlines what is expected of staff when greeting guests, setting tables, serving meals, and during work hours. A sample of the rules includes: always stand erect at your station, never against a piece of tapestry. Do not talk, laugh, or chew gum during dining room hours. When responding to a guest, you must always address a lady as “ma’am, yes ma’am, no ma’am” [sic], and a gentleman as “sir, yes sir, no sir.”

The dinners [on the written café cards with the guest’s order] should be marked according to their price: $1.00, $1.50, à la carte, or $1.25 for a fish dinner. When placing foods: meats should be placed in front of the service plate from the left side of the guest; vegetables and desserts should also be served from the left side; beverages from the right.

Waiters will assist guests on entering and leaving the dining room, helping to care for their wraps. Under no circumstances should any waitress be unfamiliar with the foods to be served. Arranging dates or appointments during duty, or with employees of another department, is not permitted [the words “during working hours” are crossed out].

At first glance, this document appears to be from the early or mid-1900s. It was typed with a mechanical typewriter, as evidenced by lighter and darker letters caused by inconsistent pressure while typing. The food prices reflect low, early inflation rates. There is no mention of stainless steel—only silverware or steel. While this may be shorthand, it could also suggest a lack of the alloy that became standard in the 1930s.

The instructions mention coffee, water, tea, and lemonade as beverages, but not soda or alcoholic drinks. Soda fountains became popular social hotspots in the mid-20th century in the United States, suggesting an earlier origin for this document. The absence of alcohol is an even stronger indicator. A fancy restaurant in the early 1900s would typically serve an extensive list of wines and spirits—except during Prohibition. Iowa enacted prohibition in 1916, which lasted until the national repeal of the 18th Amendment in 1933.

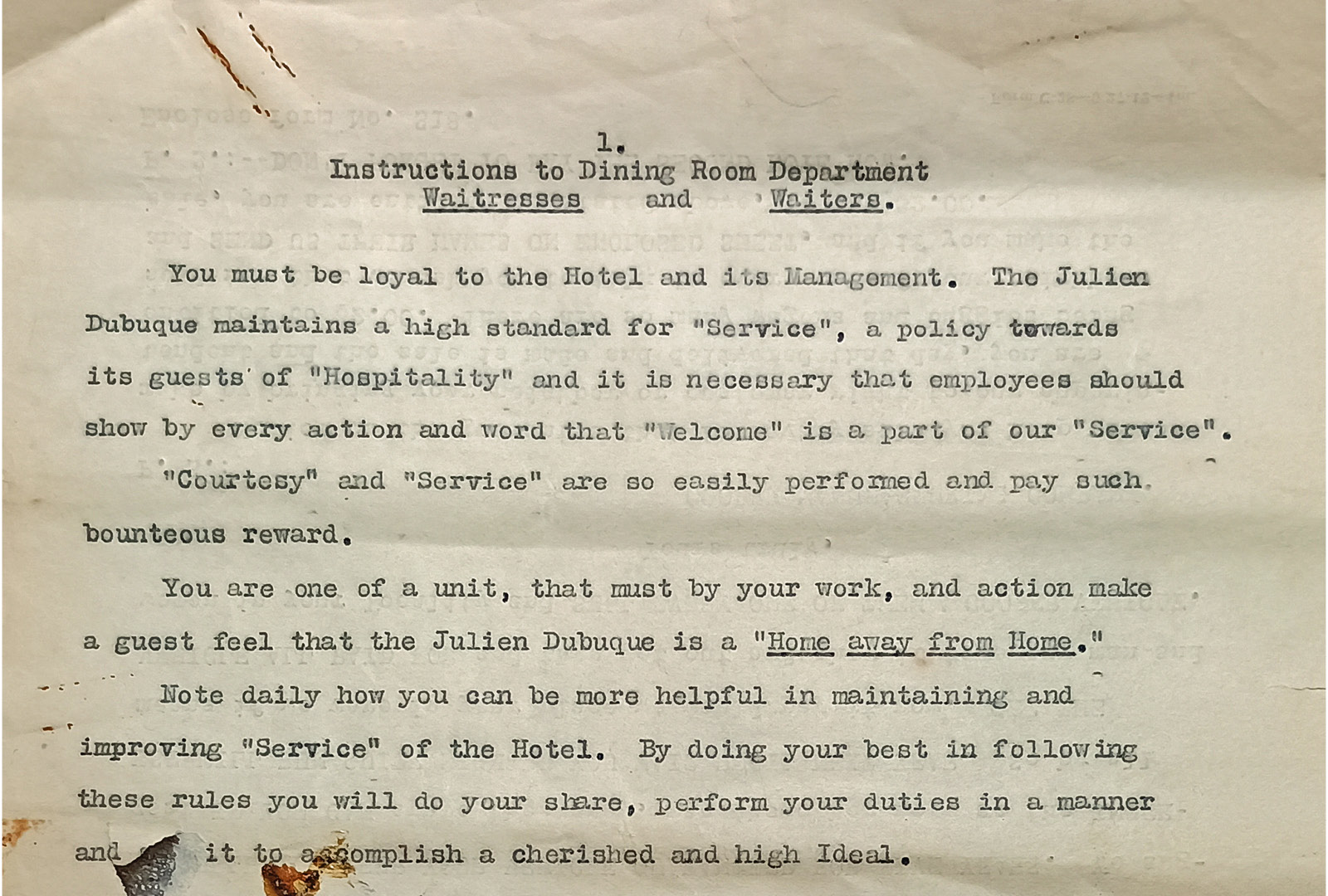

However, there is an even more defining characteristic of these pages. When turned over, the pages contain a template letter from the Cooper Manufacturing Company of Dubuque, informing the recipient that it is time to pay the second installment on a vehicle. This paper is pre-dated to the 1910s.

What does Cooper Wagon Works have to do with the Hotel Julien?

Following the death of the Cooper patriarch and company owner, A.A. Cooper, in 1919, the family closed Cooper Manufacturing. A.A. Cooper Jr. purchased stock in the Hotel Julien Dubuque for a few years, and the family managed the hotel in the 1920s ([Hotel History Fact Sheet PDF], Hotel Julien Dubuque.com). Legal action later forced A.A. Cooper Jr. to sell his shares before moving to Indiana to pursue other opportunities in hospitality. Because these instructions appear on leftover forms from the Coopers, they can be dated to about 1925 to 1933, when Prohibition ended.

These instructions were part of a gift given to the museum in memory of Lenard D. and Joan C. Heath.

To see images of the Cooper family,

To view the family’s pocket watches,